This is not the first line of an industrial joke. Among the countless mechanical miracles that came between the invention of moveable type and electronic publishing software like WordPress, there came something called the Linotype machine.

A linotype machine is the marriage of a typewriter keyboard with a metal casting plant: the operator would sit in front of the keys and type out lines, and the machine would cast them in hot lead for printing. A printer would take each line of freshly cast lead type from the machine, put it in a galley with more lines of cast words to be rolled with ink and printed on paper. Newspapers and all manner of publications once got into print this way.

Entire lines of text composed by a keyboard and cast as a single block of lead were a big step up from foundry type–which required the type setter to pick up individual letters one by one out of their compartments in a drawer to spell out words. With a Linotype machine, the operator could essentially type out the entire lead plate.

To simply say what the machine does–casting words in lead as the operator types them–doesn’t begin to capture the mechanics contained therein. Zygote Press director Liz Maugans and I saw one in action while touring Madison Press, where Cleveland letterpress guru Frank and his partner continue to run a collection of machines dating to the early twentieth century.

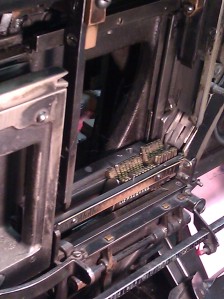

Precisely cut teeth, like the ones that make the right key work in the right lock, help each type die find its proper place in the magazine.

Their shop is not a museum but a living repository of marvelous obsolescence–a couple of modest rooms in Lakewood, packed tight with printing presses, type, and collateral contraptions all as precise as they are old. They keep them in operating condition and use them for printing jobs still best done the old fashioned way: die cuts, folding, perforating, some sequential numbering.

But even in those rooms the Linotype machine is something special. In order to do its job it has to not only melt lead into a mold known as a die, but it has to be able to change the dies in real time, according to whatever words the operator types.

For this to be useful at a newspaper, the machine needs incredible capacity, all managed mechanically, without any help from a computer: It needs to manage not just the 26 letters of the alphabet, plus numbers and punctuation, but also italics, different sizes of headline type, and more. Each individual letter is a separate die for casting lead. They need not only to line up in the proper order,

but after casting a line, they need to return to their storage places in the “magazine” so that the next time the letters are typed, they are ready to fall in line again–in an order as infinitely variable as language itself.

To understand how this happens, it helps to think of those machines that sort coins: Kids have them as piggy banks. You drop a handful of mixed coins into the hopper, and the machine sorts all the pennies, nickles, dimes, and quarters in to their proper tubes. Of course with coins, this can be done simply by size. With 26 lower case letters, 26 upper case letters, plus numbers and punctuation, it’s a bit more complicated.

The Linotype machine handles this massive sorting job a little bit like locks recognize their keys. To open a lock, it takes a key with teeth and grooves cut precisely in the right pattern to move the lock’s tumblers.

The letter dies in a linotype machine each have a set of teeth precisely cut into them, so that when they drop back into the top of a magazine, they are gravity sorted into the right slot–the one that precisely lines up with their subtle patterns of teeth.

These are primitive processes compared to what goes on when we brush fingers across a touch-screen to move pictures or words, or go from one computerized function to another. But the physical reality of these mechanical machines makes them every bit as captivating as an I-pod. Plus, they sound better. It’s no little speaker rattling out that ka-chunk-a-chunk noise; it’s a massive convolution of brass and steel.